摘 要: 衰老是一个新兴的重要研究领域,随着领域相关知识的积累和技术的进步,人们逐渐意识到衰老本身可以被针对性地干预,实现延长寿命并且延缓衰老相关疾病的发生发展,具有重要的科学和现实意义.在引起个体衰老的众多因素中,衰老细胞的积累被认为是导致器官衰老发生退行性变,最终引起衰老相关疾病的重要原因. 近年来,多项研究表明清除体内衰老细胞可以延缓多种衰老相关疾病的发生,直接证明了衰老细胞是导致衰老相关疾病的重要原因之一,为治疗衰老相关疾病提供了新靶点. 细胞衰老是由于损伤积累诱发了细胞周期抑制通路的激活,细胞永久地退出细胞增殖周期. 衰老细胞会发生细胞形态、转录谱、蛋白质稳态、表观遗传以及代谢等系列特征的改变,同时衰老细胞对凋亡发生抵抗从而在体内多器官组织积累. 衰老细胞会激活炎症因子分泌通路,导致组织局部非感染性炎症微环境,进而导致器官退行性变及多种衰老相关疾病的发生发展. 因此针对衰老细胞对凋亡抵抗的特性,多个研究小组通过筛选小分子化合物库,发现某些化合物能够选择性清除衰老细胞,这些小分子化合物被称为“senolytics”,意为“衰老细胞杀伤性化合物”. 衰老细胞杀伤性化合物在多种衰老相关疾病动物模型中能够延缓疾病的发展并延长哺乳动物寿命. 因此,靶向杀伤衰老细胞对多种衰老相关疾病的治疗从而提高健康寿命具有重要的临床应用前景. 除靶向杀伤衰老细胞策略以外,干细胞移植、基因编辑、异体共生等策略在抗衰老研究发展中也具有重要意义,具有启发性. 本文通过汇总近期衰老细胞清除领域的重要进展和多种抗衰老策略,将细胞衰老研究发展史做简要梳理,就细胞衰老与衰老相关疾病的关系作一综述,重点讨论衰老细胞在多种衰老相关疾病中作为治疗靶点的应用潜力,并就其局限性和进一步的研究方向进行探讨.

关键词: 细胞衰老; 抗衰老; 老龄化疾病; 药物靶点;

Abstract: Aging is an emerging and important research area. With the accumulation of knowledge in related fields and the advancement of technology, people gradually realized that aging itself can be intervened and it is of great scientific and practical significance to delay aging, especially delaying the occurrence and development of age-related diseases. Among the many factors that cause individual aging, the accumulation of senescent cells is considered to be an important reason that leads to organ aging and degeneration, and finally causes the age-related diseases. In recent years, a number of studies have shown that removing senescent cells in vivo can delay the occurrence of multiple age-related diseases, which directly proves that senescent cells are one of the important causes of age-related diseases, providing a new target for the treatment of age-related diseases. Cellular senescence is generally considered due to the activation of cell cycle inhibition pathway induced by accumulation of damages, and the cells permanently exit the proliferation cycle. Senescent cells undergo changes in cell morphology, transcriptional profiles, protein homeostasis, epigenome and metabolism. Moreover, senescent cells resist apoptosis and therefore accumulate in multiple organs and tissues in the body. Senescent cells secrete a number of inflammatory factors, leading to a local non-infectious inflammatory tissue microenvironment, which will cause organ function deterioration and a variety of age-related diseases. Therefore, several research groups have screened the library of small molecular compounds and found that certain compounds can selectively eliminate senescent cells by targeting pathways underpinning senescent cells' resistance to apoptosis. These small molecular compounds are called “senolytics”, denoting compounds for killing senescent cells. Senolytics have been shown to alleviate multiple age-related diseases and prolong the lifespan in animal models. Therefore, targeted killing of senescent cells has an important clinical application prospect for the treatment of a variety of age-related diseases so as to improve the healthy lifespan. In addition, strategies such as stem cell transplantation, gene editing and heterochronic parabiosis are also of great significance and inspiration in the development of anti-aging research. By summarizing the recent important progress in the field of senescent cell clearance and a variety of anti-aging strategies, this paper briefly reviews the history of cellular senescence research, discusses the relationship between cellular senescence and age-related diseases, emphasizing on the potential therapeutic applications by targeting senescent cells and the limitations, as well as the further research directions in this field.

Keyword: cellular senescence; anti-aging; age-related disease; drug target;

在个体衰老过程中,衰老细胞在组织中逐渐积累,导致组织修复能力的丧失和功能障碍的发生. 衰老细胞会激活多种炎性因子,这些炎性因子通过旁分泌导致组织微环境的恶化,从而导致各种老年性疾病的发展. 细胞衰老在多种生物学过程中发挥了重要的作用,是研究衰老的非常重要的切入点. 近年来,衰老细胞清除领域不断涌现出大量高质量的研究,为理解细胞衰老在组织器官衰老中的作用提供了实验证据,同时也为延缓衰老和衰老相关疾病提供了新的思路. 近期的研究表明,选择性清除衰老细胞可以减缓相关的组织功能障碍并延缓衰老相关性疾病的发生发展,是目前衰老领域最热门的重要研究. 本文从细胞衰老概念的提出、特性的描述、生物学意义的探究到近年来衰老细胞的多种清除方式及应用进行了系统的梳理,重点讨论了衰老细胞在多种衰老相关疾病中作为治疗靶点的应用潜力,并就其局限性和未来的发展方向进行了探讨.

1. 衰老细胞清除的研究发展史

1.1、细胞衰老的定义

1881年着名的“种质论”提出者德国动物学家Weismann提出,“死亡的发生是由于受损组织不能永久地进行自我更新,有机体中细胞分裂的能力是有限的”. 1961年,Leonard Hayflick和Paul Moorhead在人成纤维细胞的培养中发现,体外培养的细胞分裂次数是有限的[1],这也被称为“Hayflick limit”,实验证明了细胞衰老的概念. 后来的研究发现,这种类型的细胞衰老是由于细胞在不断分裂过程中端粒缩短所致[2],也被称为复制性细胞衰老(replicative senescence). 然而,有些损伤刺激如DNA损伤、致癌基因诱导、氧化应激、化疗、线粒体功能障碍和表观遗传改变等引起的细胞衰老不依赖于端粒的缩短[3],这些急性损伤导致的细胞衰老也被称为早发性细胞衰老(premature senescence). 目前,细胞衰老被定义为有丝分裂期的细胞经历内源或外源的压力损伤后永久性地退出细胞增殖周期. 而对于非增殖细胞的衰老,如静息态细胞和有丝分裂后细胞,尽管非常重要,但还没有普适的定义或特征描述. 在细胞衰老现象被明确之后,大量的研究从不同角度描述了细胞衰老的特征,包括永久性细胞周期阻滞、DNA损伤积累、凋亡抵抗、衰老相关的炎症因子分泌以及代谢和表观遗传特征改变等[4]. 因衰老具有异质性,单一的特征很难精确表征细胞衰老的发生,因此目前通常使用这一系列特征来对衰老细胞进行鉴定.

1.2、 细胞衰老与个体衰老的关系

1.2.1、衰老细胞的体内堆积

细胞衰老定义和特征被明确之后,大量研究针对衰老细胞的生物学功能展开. 目前,细胞衰老被证明在多种生物学过程中发挥着重要作用[5]. 细胞衰老对机体带来的消极影响主要通过衰老细胞的积累和恶化组织微环境实现. 在个体衰老的过程中,衰老细胞在多种组织中积累,积累的衰老细胞失去细胞原有生理功能,进而影响组织功能[6,7,8,9]. 衰老细胞也会分泌一系列炎性因子或趋化因子,称为衰老相关的分泌表型(senescence-associated secretory phenotype, SASP),SASP的产生会恶化细胞微环境[10]. 衰老细胞还可以通过自分泌或旁分泌巩固衰老表型并促进临近细胞衰老、阻碍组织再生与重塑、促进肿瘤形成,以及促进衰老相关疾病的发生发展[11,12]. 衰老细胞的堆积与众多年龄相关疾病的发生有关[13,14] ,后文中会展开讨论. 而细胞衰老对机体的积极影响主要是对短期而言,细胞在经历损伤后退出细胞周期,将组织损伤限定在一定范围内,细胞通过退出细胞周期避免成瘤,也被认为是一种抑癌机制[15,16]. 在正常组织发育和再生过程中,细胞衰老也会程序性发生. 有研究报道在蝾螈断肢再生过程中会产生衰老细胞,其被免疫细胞有效清除是蝾螈实现再生的必要条件[17]. 程序性细胞衰老参与了鸡和小鼠胚胎发育以及肢体重塑的过程,在此过程中可以检测到衰老细胞的程序性出现和清除,发育过程中细胞衰老的调控机制还有待研究[18,19,20]. 此外,在人的月经周期过程中,蜕膜化衰老细胞的产生和清除存在动态平衡,对于黄体期组织的稳态维持可能发挥了重要的作用[21]. 因此可见,细胞衰老的发生在体内是应激性或程序性的,而避免细胞衰老堆积带来的组织功能衰退和炎性微环境等负面影响是研究细胞衰老和疾病的重要切入点.

1.2.2、衰老细胞的免疫监视

衰老细胞的生物学功能逐渐清晰的同时,研究者发现机体可以通过招募免疫细胞清除衰老细胞,如前文提到的蝾螈断肢再生、哺乳动物胚胎发育过程中的组织重塑以及如肝癌[22]等一些病理条件下都检测到了衰老细胞的免疫监视和清除. 目前认为参与此过程的主要是NK细胞和巨噬细胞[23,24,25,26]. 这一过程可能是由SASP因子介导的,这些因子可以招募免疫细胞至衰老细胞并对其进行识别、杀伤与清除[27]. 清除衰老和受损细胞会为组织再生提供有利的微环境,刺激包括组织干细胞在内的邻近细胞增殖分化,重新填充受损组织,从而帮助组织修复[15]. 尽管在肝癌等病理情况下已被证明存在衰老细胞的免疫监视,但显然免疫监视在个体衰老和衰老相关疾病中效率有限,衰老细胞免疫监视的发现使人们对衰老细胞体内命运的理解更加清晰,也提供了一种通过清除衰老细胞延缓衰老和疾病的思路. 人为开发衰老细胞的清除手段并验证细胞衰老在体内的生理病理功能成为了最近5-10年中研究的重中之重.

1.2.3、清除衰老细胞有助于缓解衰老相关疾病,延长健康寿命

在细胞衰老研究的最近20年中,衰老细胞的生理病理功能逐渐被人们认识:急性的细胞衰老(acute senescence)通常是生理状态下细胞对不良刺激的抵抗,是应激性或程序性的,是有益的,生理情况下衰老细胞也可以被识别和清除. 而慢性的细胞衰老(chronic senescence)则是有害的,衰老细胞长期驻留在组织中无法得到及时清除,逐渐堆积并破坏组织微环境. 这让研究者相信清除衰老细胞可能为人们理解衰老相关疾病的防治提供一个崭新的视角.

Baker课题组在2011年首次报道了体内清除衰老细胞可以延长寿命以及延缓衰老相关疾病. 他们利用衰老细胞高表达p16Ink4a的特点建立了一种INK-ATTAC转基因小鼠,该转基因鼠在AP20187给药后会启动“自杀”基因导致p16Ink4a阳性的衰老细胞发生凋亡. 实验数据表明,AP20187处理的衰老小鼠p16Ink4a阳性衰老细胞数量减少,同时衰老相关表型发生延迟[28]. 此后,他们在两种遗传背景(C57BL/6和C57BL/6-129Sv-FVB)的INK-ATTAC转基因小鼠中证明了p16Ink4a阳性衰老细胞清除的效果. 令人震惊的是,AP20187处理后,两种遗传背景小鼠的寿命中位数均提高了24%,健康寿命分别延长了18%和25%,且AP20187能够减轻年龄相关的多种器官功能退化[29]. 利用该转基因小鼠,多个研究小组也报道了清除p16Ink4a阳性衰老细胞可以改善与年龄相关的脂肪营养不良[30]、肝脏脂肪变性[31]、心功能和骨质流失[32]以及tau介导的神经退行性变[33]. 这些研究提供了衰老细胞和衰老相关疾病的直接因果证据,为靶向杀伤衰老细胞治疗多种衰老相关疾病提供了理论依据,但其使用的转基因模型和启动药物限制了生理条件下清除衰老细胞的应用,研究者们后续聚焦在了体内清除衰老细胞的更多靶点和药物开发上.

针对衰老细胞具有抵抗凋亡的特性,研究者们试图将凋亡通路分子作为靶点,开发化合物以选择性清除衰老细胞[34,35]. 这一类型的化合物被称为“senolytics”,sen-是细胞衰老的词根,-lytic意为“裂解”,意为“衰老细胞杀伤的”. 美国明尼苏达州的梅奥医学中心(Mayo Clinic)的数个研究组在该方向做出了突出贡献. Kirkland组通过分析衰老细胞和增殖细胞的转录组,发现衰老细胞上调促进细胞存活通路的关键分子(包括肿瘤中识别的依赖受体/配体和代谢促生存转录相关元件),用siRNA沉默这些分子后可以特异性杀死衰老细胞. 该研究组利用这些分子为靶点进一步筛选了已有的化合物库后发现达沙替尼(Dasatinib, D)和槲皮素(Quercetin, Q)两种化合物,分别对衰老的脂肪前体细胞和内皮细胞具有较好的杀伤效果,给衰老小鼠联合使用D+Q可减轻多种年龄相关疾病[35]. 为了证明衰老细胞和疾病的关联,研究者将衰老的小鼠耳成纤维细胞移植到膝关节,发现可以诱发小鼠骨关节炎样的器官改变[36]. 此外,将相对较少的衰老脂肪前体细胞或耳成纤维细胞移植到年轻的小鼠腹腔就足以引起持续性的生理功能障碍,而经D+Q处理后减轻了这种衰老细胞移植诱导的生理功能障碍,提高了老年小鼠的存活率[37]. 另一类衰老细胞杀伤性化合物是基于在衰老细胞中高表达的抗凋亡BCL-2家族蛋白BCL-2、BCL-XL和BCL-W设计的[38]. 研究者发现,靶向BCL-2蛋白家族的小分子抑制剂ABT-263和ABT-737可以通过阻断BCL-2、BCL-XL和BCL-W与含有BH3结构域的促凋亡BCL-2家族蛋白的相互作用,从而选择性地清除小鼠体内的衰老细胞[39,40]. 对亚致死量辐照或正常衰老的小鼠口服给药ABT263,可以有效清除衰老的骨髓造血干细胞和衰老的肌肉干细胞,减轻全身辐照诱导的造血系统的早衰,使衰老的造血干细胞再生,并使正常衰老小鼠的衰老造血干细胞和骨髓间充质干细胞恢复活力[40]. 在另一种以p16Ink4a为基础的p16-3MR转基因小鼠中,经更昔洛韦(ganciclovir, GCV)给药清除p16Ink4a阳性的衰老内皮细胞,可减轻LDLR?/?背景小鼠动脉粥样硬化斑块的形成. 此外,对高脂饲喂的LDLR?/?小鼠给予ABT263治疗,从药理学方法上也证实了选择性清除衰老细胞可以降低动脉粥样硬化的发生[41]. 同样在该转基因小鼠中,通过前交叉韧带横截术(ACLT)制造骨关节炎模型,经GCV给药后诱导关节软骨和滑膜中的衰老细胞发生凋亡,减轻了小鼠的骨关节炎. 通过senolytics药物UBX0101清除关节软骨中的衰老细胞,也减轻了关节炎带来的疼痛,促进了软骨生长[42]. 此外Baar等人发现,衰老细胞中FOXO4蛋白高表达,且FOXO4和p53的复合物有助于维持细胞衰老的存活. 研究者设计了一种干扰FOXO4与p53相互作用的药理学肽FOXO4-DRI,可以通过p53依赖途径有效地选择性靶向清除衰老细胞,改善老年小鼠的体能、毛发生长和肾功能[43]. 这些激活衰老细胞凋亡的靶点开发极大推动了此领域的发展,揭示了衰老细胞与衰老和衰老相关疾病之间的直接联系,提示除了较为传统的抗炎类药物能够消除衰老细胞带来的炎症环境以外,清除衰老细胞可能是延长人类健康寿命和治疗衰老相关疾病的一种新策略.

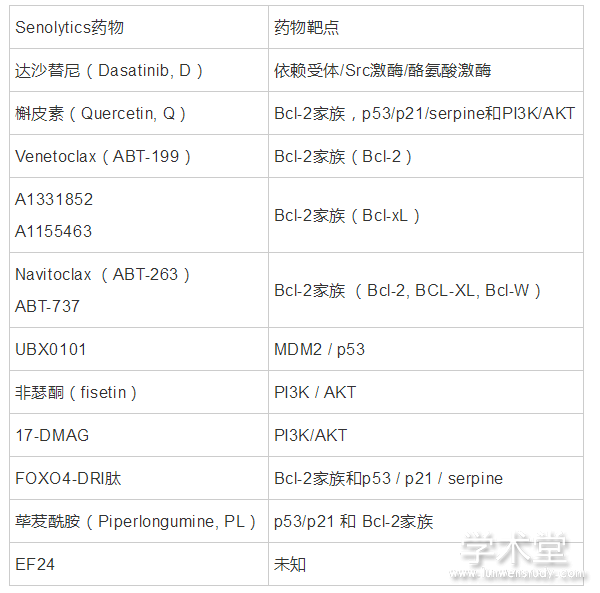

此外,还有一些senolytics药物正在被开发,如BCL-xL抑制剂A1331852和A1155463在人胚肺成纤维细胞(IMR90)和人脐静脉内皮细胞(HUVECs)中具有senolytics的作用[44]. 非瑟酮(fisetin)是一种天然的黄酮,可以选择性诱导衰老的HUVECs凋亡[44]. 荜茇酰胺(Piperlongumine, PL)在体外被发现可以诱导衰老的人WI-38成纤维细胞凋亡[45]. 但目前为止,这类化合物的实验结果多停留在体外或动物实验,并且还没有一种单独的药物选择性地诱导所有衰老细胞类型的凋亡. 表1汇总了目前主要的衰老细胞杀伤性化合物和其靶点.

表1 Senolytics药物及其作用靶点

1.2.4、清除衰老细胞的临床试验

鉴于最近五年清除衰老细胞的动物实验数据大量积累,在多种疾病模型中已经证实衰老细胞堆积是导致年龄相关疾病的重要因素,许多衰老细胞杀伤性化合物被开发出来,相关药物的临床试验也在被推进. 通过D+Q选择性清除衰老细胞治疗特发性肺纤维化的临床试验已经开展[46],该试验检测了肺纤维化病人服用D+Q药物后反应病人肺功能的步行能力. 人体试验数据表明,该药物在改善人体生理功能方面具有潜在的临床应用可能,但该临床研究没有对照组,其主要目的是评估研究的可行性而非药物疗效,因此试验结果需要谨慎看待. 最近,一项senolytics治疗糖尿病慢性肾病患者功能障碍的临床试验也正在进行中. 这次试验的中期报告结果显示,D+Q在一定程度上降低了皮肤和脂肪组织的衰老细胞负担,减少了由此产生的脂肪组织巨噬细胞的积累和循环系统中关键SASP因子的表达[47]. 但该临床试验受试者仍然较少,并且senolytics作为治疗药物的安全性尚不清楚,senolytics的作用与副作用仍需进一步的评估.

目前最有希望的senolytics似乎是BCL家族蛋白的抑制剂,这可能是由于衰老细胞需要BCL家族蛋白抵抗凋亡以获得长期生存[39,40]. 这类药物在其它类型的疾病中已经得到了临床应用,如选择性BCL-2抑制剂venetoclax(ABT-199)已用于治疗慢性淋巴细胞白血病患者[48]. 其同源的ABT-263也已进入临床试验研究,遗憾的是,ABT-263在临床试验的应用受到血小板减少症的副作用限制[49]. 最近有研究报道了一种姜黄素类似物EF24,可以选择性地促进衰老细胞中BCL-2家族蛋白降解,且与ABT263有协同作用,但EF24的作用机制尚未明确[50]. 如果其联合用药比单独用药更有效,则可能降低ABT263的用药剂量,从而降低其带来的血小板减少,提高ABT263治疗衰老相关疾病的可行性. UBX1967是另一种在临床试验中的衰老细胞杀伤性化合物,也是一种BCL-2家族抑制剂. UBX1967针对老年眼部疾病的临床试验已在美国Clinictrail.gov网站备案,其类似物UBX0101治疗骨关节炎的临床试验也在被推进中[51].

值得注意的是,鉴于这些化合物的副作用和潜在风险,目前的临床试验主要集中在较为封闭或独立的器官中,且在人体试验中是否能够与小鼠实验结果一致抵抗衰老、延长寿命尚无结论. 开发有效的方法来清除累积的衰老细胞或抑制SASP仍然是未来细胞衰老研究的重要目标之一.

2. 细胞衰老与老龄化疾病

在前面的章节中,我们简要回顾了细胞衰老领域研究发展的历程,从概念的提出、特征的描述、生物学意义探究到近来最重要的衰老细胞清除手段的开发等. 随着年龄的增长,衰老细胞在组织中积累,并可通过分泌SASP因子引起与年龄相关的病理改变. 在此章节,我们将从明确清除衰老细胞有积极作用的疾病模型着手,讨论清除衰老细胞的手段和在多种疾病中的意义.

代谢相关疾病是现代社会中发病率非常高的一类疾病. 脂肪组织的炎症与功能障碍和肥胖相关的胰岛素抵抗以及糖尿病密切相关. 近来研究者发现,衰老细胞在肥胖的人和啮齿类动物的脂肪组织中积累,而通过药物激活转基因鼠p16Ink4a启动子驱动的“自杀”基因或使用senolytics药物处理后,可以清除肥胖小鼠的衰老细胞,改善肥胖小鼠的葡萄糖耐受和炎症,从而减轻脂肪组织功能障碍[52]. 另一项研究发现ABT-199可选择性消除衰老的β细胞,而β细胞衰老是人类I型糖尿病的一个重要原因,因而在非肥胖糖尿病模型小鼠中缓解I型糖尿病的症状[53]. 这些研究表明,细胞衰老是肥胖相关的炎症和代谢紊乱以及I型糖尿病的重要原因,senolytics有望为其预防和非免疫治疗提供新的思路. 衰老细胞积累也搭建了肥胖与神经精神疾病(包括焦虑和抑郁)之间的联系. Ogrodnik等发现,肥胖小鼠脑内衰老的胶质细胞在侧脑室附近聚集,而侧脑室是成人神经发生的区域. 研究发现,通过在转基因小鼠中使用AP20187清除p16Ink4a阳性的衰老细胞,可以恢复其脑室下区神经新生,并减轻焦虑样行为. 此结果在D+Q药物处理的瘦素受体缺陷导致的肥胖小鼠模型中得以验证[54],研究者认为选择性杀伤衰老细胞也是治疗神经精神疾病的一个潜在途径.

非酒精性脂肪肝(non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD) 与肥胖和胰岛素抵抗密切相关,发病率随年龄的增长而增加,在少数患者中可导致进行性非酒精性脂肪性肝炎、纤维化,最终导致肝癌和肝功能衰竭[55]. 研究发现衰老细胞的累积促进了肝脂肪累积和脂肪变性,人为诱导肝细胞衰老可以促进脂肪在体内的积累. 在INK-ATTAC小鼠中清除p16Ink4a阳性的衰老细胞或给予D+Q处理,可以降低整体肝脂肪变性[31]. 从机理上讲,衰老细胞中的线粒体丧失了有效代谢脂肪酸的能力,因而可以导致肝脂肪变性,清除衰老细胞可能是一种减少脂肪变性的新的治疗策略.

异常tau蛋白的积累是神经退行性疾病中常见的病理原因,包括阿尔茨海默症(AD)、进行性核上性麻痹(PSP)、创伤性脑损伤(TBI)等20多种疾病[56]. 近来有研究发现,在tau介导的神经退行性疾病的小鼠模型中积累了衰老的星形胶质细胞和小胶质细胞. 在INK-ATTAC转基因小鼠中,通过给药AP20187清除这些衰老细胞可以防止胶质增生、可溶性和不溶性tau蛋白的过磷酸化导致神经纤维缠结(NFT)沉积以及皮质和海马神经元的退化,以维持认知功能[33]. 随后有研究者发现,利用D+Q也可以减少tau介导的神经退行性疾病中NFT沉积和神经退行性变[56]. 这表明衰老细胞在tau介导的神经退行性疾病的发生和发展中发挥了重要作用,提示阿尔兹海默症的预防和治疗需要在细胞衰老的大背景下重新思考.

个体衰老的一个重要表现是干细胞库的耗竭,这也是个体衰老无法避免的重要因素[57]. 衰老细胞的累积与组织特异性干细胞/祖细胞的能力下降有关. 在一项对32~86岁心血管病患者的心脏前体细胞(cardiac progenitor cells, CPCs)的分析中发现,老年受试者(> 70岁)超过一半的CPCs是衰老的,衰老的CPCs分泌的SASP因子使原本健康的CPCs衰老. 研究者通过在年老野生型小鼠中使用D+Q或在INK-ATTAC小鼠模型中清除衰老细胞,激活了驻留的CPCs,增加了Ki67、EdU阳性的心肌细胞的数量[58]. 该研究表明,清除衰老细胞可以减轻衰老带来的心脏功能恶化,恢复心肌的再生能力.

特发性肺纤维化(idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF)是一种以肺间质重塑为特征的致命性疾病,可导致肺功能受损. IPF肺中有大量的衰老生物标志物,p16的表达随着疾病的严重程度而增加. 有研究证明,衰老的成纤维细胞可以被D+Q选择性杀死,在INK-ATTAC转基因小鼠中清除衰老细胞,可以改善肺部功能和身体健康[59]. 该研究表明,肺纤维化疾病在一定程度上是由衰老细胞介导的,靶向清除衰老细胞可能是治疗人类IPF的一种新的药理学方法.

运动系统疾病也是一类高发的衰老相关疾病. 骨关节炎(osteoarthritis, OA)是一种慢性疾病,其特征是关节软骨退化,导致疼痛和身体残疾. 研究者发现OA患者的软骨细胞中存在衰老的软骨细胞,具有衰老相关的β-半乳糖苷酶(SA-β-gal)阳性染色、端粒长度缩短和线粒体变性等特征[60]. 研究者通过ACLT对小鼠制造OA模型,发现ACLT后关节软骨和滑膜中积累了衰老细胞,选择性清除这些细胞可以减轻OA的发展,减轻疼痛,提供软骨恢复的早期环境. 关节内注射senolytics分子UBX0101,在转基因、非转基因和衰老小鼠中都得到了同样的结论[42]. 此外,在全膝关节置换术患者软骨细胞的体外培养中选择性清除衰老细胞,可以降低衰老和炎症标志物的表达,同时增加软骨组织细胞外基质蛋白的表达[42,61,62,63]. 这些发现支持了衰老细胞可以作为退行性关节疾病的治疗靶点.

此外还有研究发现,退行性椎间盘细胞衰老程度以及椎间盘细胞衰老水平与人的实际年龄呈正相关[64,65],清除衰老细胞可以改善椎间盘组织内与年龄相关的多种变化[66]. 衰老细胞有望成为恢复随年龄而恶化的椎间盘组织健康的治疗靶点.

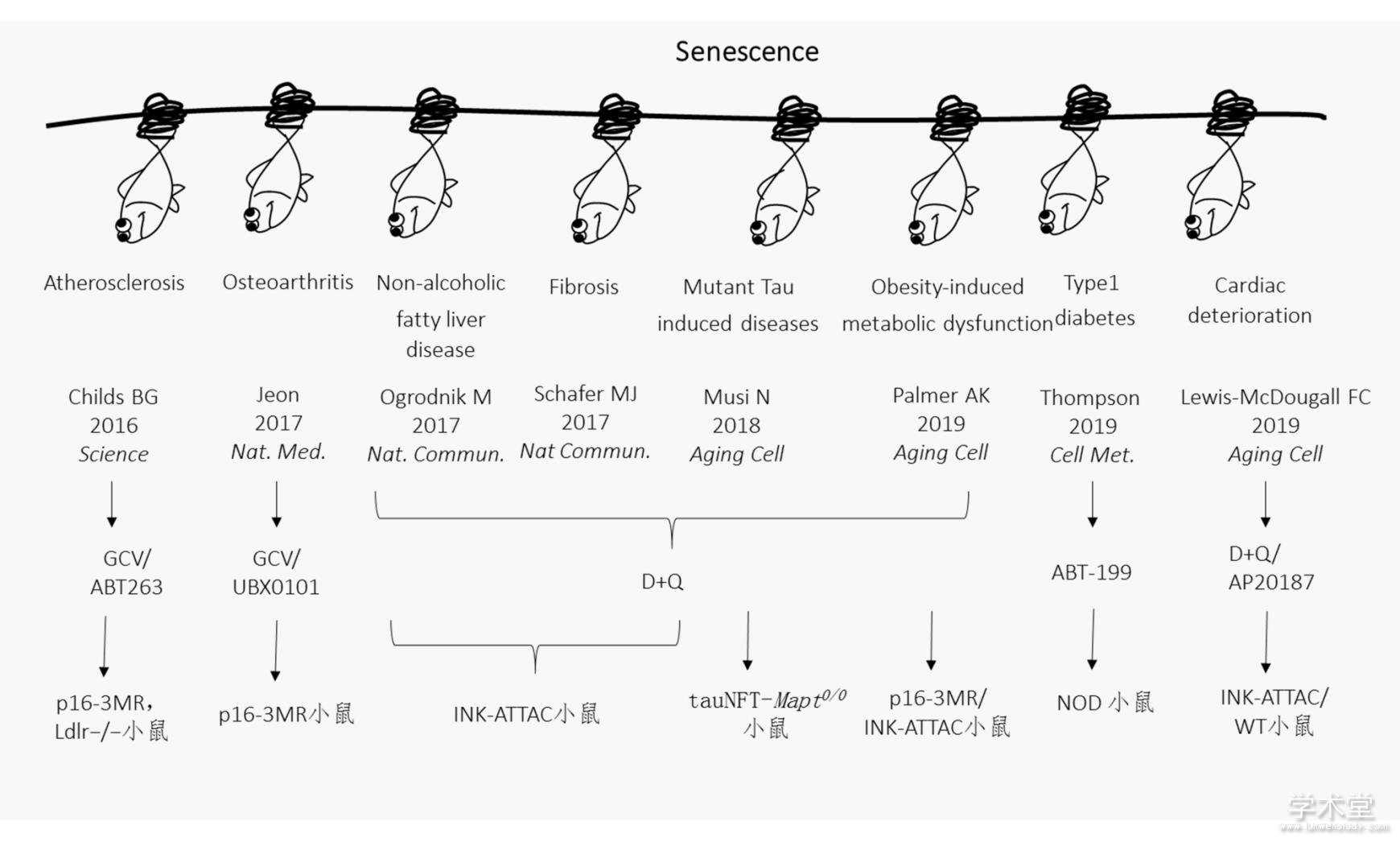

图1 清除衰老细胞在多种衰老相关疾病中被证实具有积极作用. 靶向衰老细胞可以缓解一系列衰老相关疾病,研究细胞衰老本身成为了理解衰老相关疾病发病机制的线索.

Fig.1 Clearance of senescent cells plays an active role in a variety of age-related diseases

3. Senolytics以外的抗衰老策略

Senolytics策略在最近5~10年的研究中大放异彩,研究者通过在典型的衰老相关疾病中清除衰老细胞明确了衰老细胞积累的病理意义,极大地推动了抗衰老领域的发展和社会曝光度,因该策略易于进入临床应用,研究者也对其寄予厚望. 除此以外,干细胞移植、基因编辑、异体共生等策略在抗衰老领域也具有重要的意义. 成体干细胞具有增殖分化的潜能,组织不断更新再生是一种理想的损伤修复和抵抗衰老与衰老相关疾病的思路,然而干细胞的动员和激活受到严格的调控,并且衰老的组织环境抑制干细胞的再生能力[67],除此以外,成体干细胞自身衰老也限制了组织的更新再生[68]. 在衰老过程中衰老细胞堆积和干细胞补充的平衡不断恶化,最终衰老无法挽回,因此年轻、健康、有功能的成体干细胞移植也被认为具有临床意义. 已有研究报道,干细胞移植在帕金森[69]、阿尔兹海默病[70]、骨髓瘤[71]等多种疾病中都发挥了积极作用,尤其是间充质干细胞移植已在多种疾病中进行了临床试验,包括移植物抗宿主病、自身免疫性疾病和心脏病等[72]. 近来,在通过人胚胎干细胞移植治疗老年性黄斑变性的研究中,有两例患者接受了Ⅰ期临床试验治疗[73]. 需要指出的是,细胞移植的抗衰老效用仍缺乏严谨的科学证据支持,且此类研究目前离临床应用相去甚远,要警惕社会上安全性、有效性、科学性全无的“干细胞移植疗法”乱象,不但参与者存在成瘤、排异、感染的可能性,也使公众对干细胞和抗衰老领域的科学工作产生误解. 干细胞移植策略目标集中在补充衰老个体的干细胞储备以增强再生和器官功能,一般认为无法参与清除衰老细胞和改善衰老细胞堆积造成的炎性环境等过程.

异体共生实验也是抗衰老研究中的一个重要模型,但仍存在争议. 异体共生的首次提出是在1864年,Paul Bert将两只白化病大鼠的腹部皮肤缝合在一起,发现通过吻合术连接的动物可以形成一个共享的循环系统[74]. 之后在此模型中Coleman和Friedman等研究者发现了瘦素的存在[75,76]. 2005年,Thomas Rando将破坏了肌肉和肝脏的老年小鼠分别与年轻小鼠和老年小鼠连接,发现与年轻小鼠相连的老年小鼠肌肉和肝脏的干细胞活性得到一定程度的恢复[67]. 此后一系列研究发现,异体共生对缓解老年老鼠的中枢神经系统疾病[77,78]、心肌肥厚[79]、胰腺β细胞增殖能力衰退[80]等都有积极影响. 但在2016年,Irina Conboy等研究表明,如果年轻和老年小鼠只交换血液而不共享器官,得到的结果与异体共生不同[81]. 异体共生系统中是血液中的细胞还是细胞因子发挥作用一直存在争议,也尚未明确哪种细胞或因子发挥了作用. 然而在这种背景下,美国一些公司已将输送年轻人血液抗衰老转变为商业项目,因此2019年美国FDA也在线发布警告声明,称此类项目未经过测试,没有临床证实,存在使用血浆产品相关的安全风险. 其安全性和有效性令人担忧.

此外,成体的基因编辑技术为致病基因的修正提供了可能,它与干细胞技术的结合在帕金森氏症[82]、阿尔茨海默氏症[83,84]、肌萎缩侧索硬化症[85]、亨廷顿氏症[86]等多种神经退行性疾病中都取得了进展. 儿童早衰症(Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome, HGPS)是一种致命性遗传病,主要的潜在遗传原因是lamin A的编码基因LMNA发生突变导致一种称为progerin的有毒亚型的产生,通过CRISPR-Cas9 基因编辑抑制progerin产生可以延长HGPS模型小鼠的健康寿命[87].

4. 展望与讨论

衰老是人类老年疾病的最大风险因素之一. 癌症作为一种衰老相关疾病,靶向SASP和清除衰老细胞也成为了癌症治疗的一个新的研究方向. 考虑到衰老细胞出现在癌前组织中,并通过SASP促进癌细胞发展[88],使用senolytics或SASP中和性抑制剂及时清除癌前病变中的衰老细胞可能是一种未来的化疗策略.

细胞衰老领域的研究经历了近10年的大爆炸后,诸多基础科学问题已经积累了相当的知识量,未来安全特异的衰老细胞清除手段的开发将仍是非常重要的研究方向. 特异的清除衰老细胞的方法学开发需要从衰老细胞特征着手,而目前离体衰老细胞鉴定的金标准仍是依赖衰老细胞中β-半乳糖苷酶数量和活性升高建立的化学染色,但SA-β-gal染色存在假阳性且无法针对活细胞[7,89]. 随着衰老细胞生长的停滞,细胞周期调节因子如p21和p53也通常被用于衰老细胞的检测[90],但其涉及的相关信号通路太过广谱,缺乏特异性. 相比p21和p53等细胞周期抑制因子,p16指示细胞衰老的特异性相对较好,但仍然具有局限性,并且目前尚无法实现体内原代活的衰老细胞的示踪. 尽管衰老细胞分泌的SASP是其重要的特征,但并未发现特异的炎症因子可以精确反应细胞衰老,因此难以定量或与其他炎性区分.

除已知的衰老细胞抵抗凋亡的靶点外,其他衰老细胞清除手段的开发在未来一段时间值得关注,如Gorospe研究小组发现DPP4(也被称为CD26)在衰老的人成纤维细胞中高表达,并且衰老细胞被能识别抗DPP4抗体的NK细胞优先清除[91],这对衰老细胞清除手段的开发具有启发性. 除此之外,纳米药物系统也已被用于靶向特发性肺纤维化的衰老细胞[92]. 一些新的靶向衰老细胞的药物靶点正在被开发,但由于细胞衰老的进行性和组织器官的异质性,目前仍然没有非常特异和普适性的衰老细胞标志物和药物靶点.

除了清除衰老细胞的手段非常值得被开发以外,目前细胞衰老的研究主要集中在有丝分裂细胞,对于有丝分裂后细胞和静息态细胞而言,细胞衰老的生物学功能也亟待被探讨. 自20世纪50年代末以来,一些研究小组报道了脂褐素在有丝分裂后或终末分化细胞类型(如神经元和心肌细胞)中的年龄依赖性积累[93,94,95],但其应用一直没有得到推进. 目前学界认为有丝分裂后细胞也存在细胞衰老,但有丝分裂后细胞衰老(postmitotic cell senescence, PoMiCS)对组织结构和功能的影响尚不明确. 有研究表明,在正常衰老过程中,小鼠皮层、海马、浦肯野等有丝分裂后的中枢神经细胞以及周围神经元均表现出细胞衰老的特征,如类似的衰老相关分泌表型和周期阻滞因子表达[96]. 视网膜的中枢神经系统组织中存在大量PoMiCS,并且衰老的视网膜神经元可以通过旁分泌神经血管导向因子SEMA3A,在体外诱导视网膜神经元、巨噬细胞样基质细胞和内皮细胞的衰老[97]. 骨细胞是另一类有丝分裂后细胞,在正常衰老的小鼠中,有丝分裂后的骨细胞和成骨细胞中p16Ink4a表达升高,且p16Ink4a和SASP因子在老年人骨活检中均升高[98],提示骨组织中同样存在PoMiCS并可能通过分泌SASP导致疾病的进展. 但在以有丝分裂后细胞为主的组织中,PoMiCS也被证实可以抵抗应激引起的组织变性,促进组织修复[99],因而此领域还存在较大的知识空白.

综上所述,清除衰老细胞在衰老和衰老相关疾病中的研究有令人兴奋的实质性进展,目前衰老研究的模式动物也已经从上世纪的线虫、果蝇逐渐集中在了以小鼠或大鼠为主的哺乳动物模型. 值得一提的是,在啮齿类动物中被证实与寿命延长相关的基因与果蝇、线虫甚至人类中并非总是一致[100,101,102],啮齿类哺乳动物中的研究结果能否适用于人类仍然未知. 针对物种间保守的信号通路和分子细胞机制,其中一部分可能可以应用于人[103],但要严格考量其分子细胞机制、剂量、有效性以及安全性. 关于实验动物和人类的寿命差异与抗衰老研究,以下几点也要慎重考虑:一是在“氧化自由基学说”背景下啮齿类动物与人类代谢、体重的差异可能是二者寿命差异的原因之一;二是同种实验动物之间的遗传背景相近,而人类群体基因库存在如单核苷酸多态性等遗传异质性,导致个体的寿命以及对不同衰老相关疾病的易感性差异,因此针对不同遗传背景的抗衰老策略可能不同,应在精准医学的背景下思考这一问题.

参考文献

[1] Hayflick L, Moorhead P S. Serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res, 1961, 25(3): 585-621.

[2] Sharpless N E, Sherr C J. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2015, 15(7): 397.

[3] Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends in Cell Biology, 2018, 28(6): 436-453.

[4] Kirkland J L, Tchkonia T. Cellular senescence: A translational perspective. EBioMedicine, 2017, 21(21-28.

[5] He S, Sharpless N E. Senescence in health and disease. Cell, 2017, 169(6): 1000-1011.

[6] Faragher R G A, Kipling D. How might replicative senescence contribute to human ageing? BioEssays, 1998, 20(12): 985-991.

[7] Dimri G P, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995, 9363-9367.

[8] Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey M R, et al. Ink4a/arf expression is a biomarker of aging. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2004, 114(9): 1299-1307.

[9] Gruber H E, Ingram J A, H James N, et al. Senescence in cells of the aging and degenerating intervertebral disc: Immunolocalization of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase in human and sand rat discs. Spine, 2007, 32(3): 321-327.

[10] Acosta J C, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nature cell biology, 2013, 15(8): 978-990.

[11] Borodkina A V, Deryabin P I, Giukova A A, et al. "Social life" of senescent cells: What is sasp and why study it? Acta Naturae, 2018, 10(1): 4-14.

[12] Childs B G, Durik M, Baker D J, et al. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nature medicine, 2015, 21(1424.

[13] Burton D G A. Cellular senescence, ageing and disease. AGE, 2009, 31(1): 1-9.

[14] Mu?oz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2014, 15(482.

[15] Marco D, Naoko O, Youssef S A, et al. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of pdgf-aa. Developmental Cell, 2014, 31(6): 722-733.

[16] Aravinthan A, Challis B, Shannon N, et al. Selective insulin resistance in hepatocyte senescence. Exp Cell Res, 2015, 331(1): 38-45.

[17] Yun M H, Davaapil H, Brockes J P. Recurrent turnover of senescent cells during regeneration of a complex structure. eLife, 2015, 4(e05505.

[18] Storer M, Mas A, Robert-Moreno A, et al. Senescence is a developmental mechanism that contributes to embryonic growth and patterning. Cell, 2013, 155(5): 1119-1130.

[19] Mu?oz-Espín D, Ca?amero M, Maraver A, et al. Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development. Cell, 2013, 155(5): 1104-1118.

[20] 刘俊平. 衰老及相关疾病细胞分子机制研究进展. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2014, 41(3): 215-230.

[21] Brighton P J, Maruyama Y, Fishwick K, et al. Clearance of senescent decidual cells by uterine natural killer cells in cycling human endometrium. eLife, 2017, 6(e31274.

[22] Kang T-W, Yevsa T, Woller N, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature, 2011, 479(547.

[23] Jackaman C, Tomay F, Duong L, et al. Aging and cancer: The role of macrophages and neutrophils. Ageing research reviews, 2017, 36(105-116.

[24] Pereira B I, Devine O P, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, et al. Senescent cells evade immune clearance via hla-e-mediated nk and cd8(+) t cell inhibition. Nature communications, 2019, 10(1): 2387-2387.

[25] Sagiv A, Biran A, Yon M, et al. Granule exocytosis mediates immune surveillance of senescent cells. Oncogene, 2013, 32(15): 1971-1977.

[26] Sagiv A, Burton D G A, Moshayev Z, et al. Nkg2d ligands mediate immunosurveillance of senescent cells. Aging, 2016, 8(2): 328-344.

[27] Solana R, Tarazona R, Gayoso I, et al. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Seminars in Immunology, 2012, 24(5): 331-341.

[28] Baker D J, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, et al. Clearance of p16ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature, 2011, 479(7372): 232-236.

[29] Baker D J, Childs B G, Durik M, et al. Naturally occurring p16(ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature, 2016, 530(7589): 184-189.

[30] Xu M, Palmer A K, Ding H, et al. Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. eLife, 2015, 4(e12997-e12997.

[31] Ogrodnik M, Miwa S, Tchkonia T, et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nature communications, 2017, 8(15691-15691.

[32] Farr J N, Xu M, Weivoda M M, et al. Targeting cellular senescence prevents age-related bone loss in mice. Nature medicine, 2017, 23(9): 1072-1079.

[33] Bussian T J, Aziz A, Meyer C F, et al. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature, 2018, 562(7728): 578-582.

[34] Childs B G, Baker D J, Kirkland J L, et al. Senescence and apoptosis: Dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep, 2014, 15(11): 1139-1153.

[35] Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, et al. The achilles' heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging cell, 2015, 14(4): 644-658.

[36] Xu M, Bradley E W, Weivoda M M, et al. Transplanted senescent cells induce an osteoarthritis-like condition in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2017, 72(6): 780-785.

[37] Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr J N, et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nature medicine, 2018, 24(8): 1246-1256.

[38] Claudia C, Cindy G, Mario D, et al. Roles of apoptosis and cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Current Drug Targets, 2016, 17(4): 405-415.

[39] Yosef R, Pilpel N, Tokarsky-Amiel R, et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of bcl-w and bcl-xl. Nature communications, 2016, 7(11190-11190.

[40] Chang J, Wang Y, Shao L, et al. Clearance of senescent cells by abt263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nature medicine, 2016, 22(1): 78-83.

[41] Childs B G, Baker D J, Wijshake T, et al. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science (New York, NY), 2016, 354(6311): 472-477.

[42] Jeon O H, Kim C, Laberge R-M, et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nature medicine, 2017, 23(6): 775-781.

[43] Baar M P, Brandt R M C, Putavet D A, et al. Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell, 2017, 169(1): 132-147.e116.

[44] Zhu Y, Doornebal E J, Pirtskhalava T, et al. New agents that target senescent cells: The flavone, fisetin, and the bcl-x(l) inhibitors, a1331852 and a1155463. Aging, 2017, 9(3): 955-963.

[45] Wang Y, Chang J, Liu X, et al. Discovery of piperlongumine as a potential novel lead for the development of senolytic agents. Aging, 2016, 8(11): 2915-2926.

[46] Justice J N, Nambiar A M, Tchkonia T, et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine, 2019, 40(554-563.

[47] Hickson L J, Langhi Prata L G P, Bobart S A, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of dasatinib plus quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine, 2019, 47(446-456.

[48] Roberts A W, Davids M S, Pagel J M, et al. Targeting bcl2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015, 374(4): 311-322.

[49] Vogler M, Hamali H A, Sun X-M, et al. Bcl2/bcl-x<sub>l</sub> inhibition induces apoptosis, disrupts cellular calcium homeostasis, and prevents platelet activation. Blood, 2011, 117(26): 7145-7154.

[50] Li W, He Y, Zhang R, et al. The curcumin analog ef24 is a novel senolytic agent. Aging, 2019, 11(2): 771-782.

[51] Van Deursen J M. Senolytic therapies for healthy longevity. Science, 2019, 364(6441): 636-637.

[52] Palmer A K, Xu M, Zhu Y, et al. Targeting senescent cells alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. Aging Cell, 2019, 18(3): e12950-e12950.

[53] Thompson P J, Shah A, Ntranos V, et al. Targeted elimination of senescent beta cells prevents type 1 diabetes. Cell metabolism, 2019, 29(5): 1045-1060.e1010.

[54] Ogrodnik M, Zhu Y, Langhi L G P, et al. Obesity-induced cellular senescence drives anxiety and impairs neurogenesis. Cell metabolism, 2019, 29(5): 1061-1077 e1068.

[55] Hardy T, Oakley F, Anstee Q M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathogenesis and disease spectrum. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 2016, 11(1): 451-496.

[56] Musi N, Valentine J M, Sickora K R, et al. Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain. Aging cell, 2018, 17(6): e12840-e12840.

[57] 安瑞, 易微微, 鞠振宇. 造血干细胞衰老的研究进展. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2014, 41(3): 238-246.

[58] Lewis-Mcdougall F C, Ruchaya P J, Domenjo-Vila E, et al. Aged-senescent cells contribute to impaired heart regeneration. Aging Cell, 0(0): e12931.

[59] Schafer M J, White T A, Iijima K, et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nature communications, 2017, 8(14532-14532.

[60] Mcculloch K, Litherland G J, Rai T S. Cellular senescence in osteoarthritis pathology. Aging cell, 2017, 16(2): 210-218.

[61] Loeser R F. Aging and osteoarthritis: The role of chondrocyte senescence and aging changes in the cartilage matrix. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 2009, 17(8): 971-979.

[62] Price J S, Waters J G, Darrah C, et al. The role of chondrocyte senescence in osteoarthritis. Aging Cell, 2002, 1(1): 57-65.

[63] Martin J A, Brown T D, Heiner A D, et al. Chondrocyte senescence, joint loading and osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research, 2004, 427(427 Suppl): S96.

[64] Gruber H E, Ingram J A, Davis D E, et al. Increased cell senescence is associated with decreased cell proliferation in vivo in the degenerating human annulus. Spine Journal Official Journal of the North American Spine Society, 2009, 9(3): 210-215.

[65] Le Maitre C L, Freemont A J, Hoyland J A. Accelerated cellular senescence in degenerate intervertebral discs: A possible role in the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Arthritis research & therapy, 2007, 9(3): R45-R45.

[66] Patil P, Dong Q, Wang D, et al. Systemic clearance of p16ink4a-positive senescent cells mitigates age-associated intervertebral disc degeneration. Aging Cell, 0(0): e12927.

[67] Conboy I M, Conboy M J, Wagers A J, et al. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature, 2005, 433(7027): 760-764.

[68] Rossi D J, Jamieson C H M, Weissman I L. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell, 2008, 132(4): 681-696.

[69] Sundberg M, Isacson O. Advances in stem-cell–generated transplantation therapy for parkinson's disease. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 2014, 14(4): 437-453.

[70] Duncan T, Valenzuela M. Alzheimer's disease, dementia, and stem cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2017, 8(1): 111-111.

[71] Maybury B, Cook G, Pratt G, et al. Augmenting autologous stem cell transplantation to improve outcomes in myeloma. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2016, 22(11): 1926-1937.

[72] Wang S, Qu X, Zhao R C. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 2012, 5(1): 19.

[73] Da Cruz L, Fynes K, Georgiadis O, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration. Nature Biotechnology, 2018, 36(328.

[74] Bert P. Expériences et considérations sur la greffe animale. Journal de l'Anatomie et de la Physiologie, 1(69-87.

[75] Coleman D L. A historical perspective on leptin. Nature medicine, 2010, 16(10): 1097-1099.

[76] Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature, 1994, 372(6505): 425-432.

[77] Villeda S A, Luo J, Mosher K I, et al. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature, 2011, 477(7362): 90-94.

[78] Ruckh J M, Zhao J-W, Shadrach J L, et al. Rejuvenation of regeneration in the aging central nervous system. Cell stem cell, 2012, 10(1): 96-103.

[79] Loffredo F S, Steinhauser M L, Jay S M, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell, 2013, 153(4): 828-839.

[80] Salpeter S J, Khalaileh A, Weinberg-Corem N, et al. Systemic regulation of the age-related decline of pancreatic β-cell replication. Diabetes, 2013, 62(8): 2843-2848.

[81] Rebo J, Mehdipour M, Gathwala R, et al. A single heterochronic blood exchange reveals rapid inhibition of multiple tissues by old blood. Nature communications, 2016, 7(13363-13363.

[82] Liu G-H, Qu J, Suzuki K, et al. Progressive degeneration of human neural stem cells caused by pathogenic lrrk2. Nature, 2012, 491(7425): 603-607.

[83] Muratore C R, Rice H C, Srikanth P, et al. The familial alzheimer's disease appv717i mutation alters app processing and tau expression in ipsc-derived neurons. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(13): 3523-3536.

[84] Yahata N, Asai M, Kitaoka S, et al. Anti-aβ drug screening platform using human ips cell-derived neurons for the treatment of alzheimer's disease. PloS one, 2011, 6(9): e25788-e25788.

[85] Chen H, Qian K, Du Z, et al. Modeling als with ipscs reveals that mutant sod1 misregulates neurofilament balance in motor neurons. Cell stem cell, 2014, 14(6): 796-809.

[86] An M C, Zhang N, Scott G, et al. Genetic correction of huntington's disease phenotypes in induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell stem cell, 2012, 11(2): 253-263.

[87] Beyret E, Liao H-K, Yamamoto M, et al. Single-dose crispr-cas9 therapy extends lifespan of mice with hutchinson-gilford progeria syndrome. Nature medicine, 2019, 25(3): 419-422.

[88] Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, Van Deursen J, et al. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: Therapeutic opportunities. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2013, 123(3): 966-972.

[89] Florence D C, Erusalimsky J D, Judith C, et al. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (sa-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nature Protocols, 2009, 4(12): 1798.

[90] Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: Evidence from mice and humans. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2010, 10(51.

[91] Kim K M, Noh J H, Bodogai M, et al. Identification of senescent cell surface targetable protein dpp4. Genes & development, 2017, 31(15): 1529-1534.

[92] Mu?oz-Espín D, Rovira M, Galiana I, et al. A versatile drug delivery system targeting senescent cells. Embo Molecular Medicine, 2018, 10(9): e9355.

[93] Reichel W. Lipofuscin pigment accumulation and distribution in five rat organs as a function of age. Journal of Gerontology, 1968, 23(1): 71.

[94] Reichel W, Hollander J, Clark J H, et al. Lipofuscin pigment accumulation as a function of age and distribution in rodent brain. Journal of Gerontology, 23(1): 71.

[95] Strehler B L, Mark D D, Mildvan A S. Gee mv: Rate and magnitude of age pigment accumulation in the human myocardium. Journal of Gerontology, 1959, 14(4): 430.

[96] Jurk D, Wang C, Miwa S, et al. Postmitotic neurons develop a p21-dependent senescence-like phenotype driven by a DNA damage response. Aging cell, 2012, 11(6): 996-1004.

[97] Oubaha M, Miloudi K, Dejda A, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype contributes to pathological angiogenesis in retinopathy. Science Translational Medicine, 2016, 8(362): 362ra144-362ra144.

[98] Farr J N, Fraser D G, Wang H, et al. Identification of senescent cells in the bone microenvironment. J Bone Miner Res, 2016, 31(11): 1920-1929.

[99] Sapieha P, Mallette F A. Cellular senescence in postmitotic cells: Beyond growth arrest. Trends in Cell Biology, 2018, 28(8): 595-607.

[100] Jo?O Pedro D M E. Why genes extending lifespan in model organisms have not been consistently associated with human longevity and what it means to translation research. Cell Cycle, 2014, 13(17): 2671-2673.

[101] Jones O R, Scheuerlein A, Salguero-Gómez R, et al. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Nature, 2014, 505(7482): 169-173.

[102] Kim S K. Common aging pathways in worms, flies, mice and humans. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2007, 210(9): 1607-1612.

[103] Kenyon C, . A conserved regulatory system for aging. Cell, 2001, 105(2): 165-168.