参考文献

[1] Manoli E., Samara, C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in natural waters sources, occurrence andanalysis [J]. Trac Trends Anal Chem, 1999, 18(6): 417-428.

[2] Liu Y., Yan C., Ding X., Wang X., Fu Q., Zhao Q., Zhang Y., Duan Y., Qiu X., Zheng M. Sourcesand spatial distribution of particulate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Shanghai, China [J]. SciTotal Environ, 2017, 584-585: 307-317.

[3] Ravindra K., Sokhi R., Vangrieken R. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Sourceattribution, emission factors and regulation [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2008, 42(13): 2895-921.

[4] Lin Y., Ma Y., Qiu X., Li R., Fang Y., Wang J., Zhu Y., Hu D. Sources, transformation, and healthimplications of PAHs and their nitrated, hydroxylated, and oxygenated derivatives in PM2.5inBeijing [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2015, 120(14): 7219-7228.

[5] Beriro D. J., Cave M. R., Wragg J., Thomas R., Wills G., Evans F. A review of the current state ofthe art of physiologically-based tests for measuring human dermal in vitro bioavailability ofpolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in soil [J]. J Hazard Mater, 2016, 305: 240-259.

[6] Ruby M. V., Lowney Y. W. Selective soil particle adherence to hands: implications forunderstanding oral exposure to soil contaminants [J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2012, 46(23): 12759-12771.

[7] Menezes H. C., De Barcelos S. M., Macedo D. F., Purceno A. D., Machado B. F., Teixeira A. P.,Lago R. M., Serp P., Cardeal Z. L. Magnetic N-doped carbon nanotubes: A versatile and efficientmaterial for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental water samples[J]. Anal Chim Acta, 2015, 873: 51-56.

[8] Nielsen K., Kalmykova Y., Stromvall A. M., Baun A., Eriksson E. Particle phase distribution ofpolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in stormwater--Using humic acid and iron nano-sized colloids astest particles [J]. Sci Total Environ, 2015, 532: 103-111.

[9] Ma Y., Harrad S. Spatiotemporal analysis and human exposure assessment on polycyclic aromatichydrocarbons in indoor air, settled house dust, and diet: A review [J]. Environ Int, 2015, 84: 7-16.

[10] Xu J., Peng X., Guo C. S., Xu J., Lin H. X., Shi G. L., Lv J. P., Zhang Y., Feng Y. C., Tysklind M.Sediment PAH source apportionment in the Liaohe River using the ME2 approach: A comparisonto the PMF model [J]. Sci Total Environ, 2016, 553: 164-171.

[11] Bansal V., Kim K. H. Review of PAH contamination in food products and their health hazards

[J].Environ Int, 2015, 84: 26-38.

[12] Suzuki K., Yoshinaga J. Inhalation and dietary exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons andurinary 1-hydroxypyrene in non-smoking university students [J]. Int Arch Occup Environ Health,2007, 81(1): 115-121.

[13] Yang P., Sun H., Gong Y. J., Wang Y. X., Liu C., Chen Y. J., Sun L., Huang L. L., Ai S. H., Lu W.Q., Zeng Q. Repeated measures of urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites in relation to altered reproductive hormones: A cross-sectional study in China [J]. Int J Hyg Environ Health,2017, 220(8): 1340-1346.

[14] Hoseini M., Nabizadeh R., Delgado-Saborit J. M., Rafiee A., Yaghmaeian K., Parmy S., Faridi S.,Hassanvand M. S., Yunesian M., Naddafi K. Environmental and lifestyle factors affecting exposureto polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the general population in a Middle Eastern area [J]. EnvironPollut, 2018, 240: 781-792.

[15] Desai G., Chu L., Guo Y., Myneni A. A., Mu L. Biomarkers used in studying air pollution exposureduring pregnancy and perinatal outcomes: a review [J]. Biomarkers, 2017, 22(6): 489-501.

[16] Gunier R. B., Reynolds P., Hurley S. E., Yerabati S., Hertz A., Strickland P., Horn-Ross P. L.

Estimating exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a comparison of survey, biologicalmonitoring, and geographic information system-based methods [J]. Cancer Epidemiol BiomarkersPrev, 2006, 15(7): 1376-1381.

[17] Bach Pb K. M., Tate Rc, Mccrory Dc. Screening for Lung Cancer: A Review of the CurrentLiterature [J]. Chest, 2003, 123(1): 72S-82S.

[18] Diggs D. L., Huderson A. C., Harris K. L., Myers J. N., Banks L. D., Rekhadevi P. V., Niaz M. S.,Ramesh A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and digestive tract cancers: a perspective [J]. JEnviron Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev, 2011, 29(4): 324-357.

[19] Kim K. H., Jahan S. A., Kabir E., Brown R. J. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatichydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects [J]. Environ Int, 2013, 60: 71-80.

[20] Olsson A. C., Fevotte J., Fletcher T., Cassidy A., T Mannetje A., Zaridze D., Szeszenia-DabrowskaN., Rudnai P., Lissowska J., Fabianova E., Mates D., Bencko V., Foretova L., Janout V., BrennanP., Boffetta P. Occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lung cancer risk: amulticenter study in Europe [J]. Occup Environ Med, 2010, 67(2): 98-103.

[21] Mumtaz MM, George JD, Gold KW,Cibulas W,DeRosa CT. Atsdr evaluation of health effects ofchemicals. Iv. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) understanding a complex problem [J].Toxicology and Industrial Health, 1996, 12(6): 742-995.

[22] Perera F. P., Rauh V., Whyatt R. M., Tsai W. Y., Tang D., Diaz D., Hoepner L., Barr D., Tu Y. H.,Camann D., Kinney P. Effect of prenatal exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons onneurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children [J]. Environ Health Perspect,2006, 114(8): 1287-1292.

[23] Wormley D. D., Chirwa S., Nayyar T., Wu J., Cellular D. B. H. J., Biology M. Inhaledbenzo(a)pyrene impairs long-term potentiation in the F1 generation rat dentate gyrus [J]. 2004,50(6): 715-721.

[24] Brown L. A., Khousbouei H., Goodwin J. S., Irvin-Wilson C. V., Ramesh A., Sheng L., MccallisterM. M., Jiang G. C., Aschner M., Hood D. B. Down-regulation of early ionotrophic glutamatereceptor subunit developmental expression as a mechanism for observed plasticity deficitsfollowing gestational exposure to benzo(a)pyrene [J]. Neurotoxicology, 2007, 28(5): 965-978.

[25] Chongying Qiu, Tu A. B. The Effect of Occupational Exposure to Benzo[a]pyrene onNeurobehavioral Function in Coke Oven Workers [J]. American Journal of Industrial Medicine,2013, 56: 347-355.

[26] Niu Q., Zhang H., Li X., Li M. Benzo[a]pyrene-induced neurobehavioral function andneurotransmitter alterations in coke oven workers [J]. Occup Environ Med, 2010, 67(7): 444-448.

[27] 聂继盛,张红梅,孙建娅. 焦炉作业工人神经行为功能改变的特征分析 [J]. 中华预防医学,2008, 42(1): 25-29.

[28] Chen C., Tang Y., Jiang X., Qi Y., Cheng S., Qiu C., Peng B., Tu B. Early postnatal benzo(a)pyreneexposure in Sprague-Dawley rats causes persistent neurobehavioral impairments that emergepostnatally and continue into adolescence and adulthood [J]. Toxicol Sci, 2012, 125(1): 248-261.

[29] Costa L. G., Cole T. B., Dao K., Chang Y. C., Coburn J., Garrick J. M. Effects of air pollution onthe nervous system and its possible role in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2020, 107523.

[30] Yuchi W., Sbihi H., Davies H., Tamburic L., Brauer M. Road proximity, air pollution, noise, greenspace and neurologic disease incidence: a population-based cohort study [J]. Environ Health, 2020,19(8): 1-15.

[31] Oudin A., Andersson J., Sundstrom A., Nordin Adolfsson A., Oudin Astrom D., Adolfsson R.,Forsberg B., Nordin M. Traffic-Related Air Pollution as a Risk Factor for Dementia: No ClearModifying Effects of APOEvarepsilon4 in the Betula Cohort [J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2019, 71(3):733-740.

[32] Nie J., Duan L., Yan Z., Niu Q. Tau hyperphosphorylation is associated with spatial learning andmemory after exposure to benzo[a]pyrene in SD rats [J]. Neurotox Res, 2013, 24(4): 461-471.

[33] Kim K. R., Lee K. S., Cheong H. K., Eom J. S., Oh B. H., Hong C. H. Characteristic profiles ofinstrumental activities of daily living in different subtypes of mild cognitive impairment [J].Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2009, 27(3): 278-285.

[34] Goldman J. G., Holden S. K., Litvan I., Mckeith I., Stebbins G. T., Taylor J. P. Evolution ofdiagnostic criteria and assessments for Parkinson's disease mild cognitive impairment [J]. MovDisord, 2018, 33(4): 503-510.

[35] Calderon-Garciduenas L., Engle R., Mora-Tiscareno A., Styner M., Gomez-Garza G., Zhu H.,Jewells V., Torres-Jardon R., Romero L., Monroy-Acosta M. E., Bryant C., Gonzalez-Gonzalez L.O., Medina-Cortina H., D'angiulli A. Exposure to severe urban air pollution influences cognitiveoutcomes, brain volume and systemic inflammation in clinically healthy children [J]. Brain Cogn,2011, 77(3): 345-355.

[36] Calderon-Garciduenas L., Torres-Jardon R., Kulesza R. J., Mansour Y., Gonzalez-Gonzalez L. O.,Gonzalez-Maciel A., Reynoso-Robles R., Mukherjee P. S. Alzheimer disease starts in childhood inpolluted Metropolitan Mexico City. A major health crisis in progress [J]. Environ Res, 2020, 183:109137.

[37] Ailshire J. A., Clarke P. Fine particulate matter air pollution and cognitive function among U.S.older adults [J]. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 2015, 70(2): 322-328.

[38] Calderon-Garciduenas L., Mukherjee P. S., Kulesza R. J., Torres-Jardon R., Hernandez-Luna J.,Avila-Cervantes R., Macias-Escobedo E., Gonzalez-Gonzalez O., Gonzalez-Maciel A., Garcia-Hernandez K., Hernandez-Castillo A., Villarreal-Rios R., Research Universidad Del Valle DeMexico U. V. M. G. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Involving Multiple CognitiveDomains in Mexican Urbanites [J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2019, 68(3): 1113-1123.

[39] Lilian C. G. A., Angélica G.-M., Rafael R.-R., J. K. R. Alzheimer's disease and alpha-synucleinpathology in the olfactory bulbs of infants, children, teens and adults <40 years in MetropolitanMexico City. APOE4 carriers at higher risk of suicide accelerate their olfactory bulb pathology [J].Environmental Research, 2018, 166(2018): 348-362.

[40] Folstein Mf F. S., Mchugh Pr,. “Mini-mental state” a practical method for grading the cognitivestate of patients for the clinician [J]. J Psychiatr Res, 1975, 12(3): 189-198.

[41] Angevaren M A G., Verhaar H j, Aleman A, Vanhees L,. Physical activity and enhanced fitness toimprove cognitivefunction in older people without known cognitive impairment [J]. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev 2008, 16(3): T486-T486.

[42] Nasreddine Zs P. N., Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings Jl. Briemethodological reportsthe montreal cognitive assessment, MOCA a brief screeningtool for mildcognitive impairment [J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53(4): 695-699.

[43] Luis C. A., Keegan A. P., Mullan M. Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment incommunity dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US [J]. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2009,24(2): 197-201.

[44] Lebedeva E, Huang M, Koski L,. Comparison of Alternate and Original Items on the MontrealCognitive Assessment [J]. 2016, 19(1): 15-18.

[45] Julayanont P., Phillips N., Chertkow H., Nasreddine Z. S. J. C. S. I. Montreal Cognitive Assessment(MoCA): Concept and Clinical Review [J]. 2013.

[46] Huang J. Y. J. L. X. The Beijing version of the montreal cognitiveassessment as a brief screeningtool for mildcognitive impairment: a community-based study [J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2012, 12(156):2-8.

[47] Wk A. Neurobehavioural tests and systems to assess neurotoxic exposures in the workplace andcommunity [J]. Occup Environ Med 2003, 60: 531-548.

[48] Yang J., Zhang Z., Zhang L., Su Y., Sun Y., Wang Q. Relationship Between Self-Care Behavior andCognitive Function in Hospitalized Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Stud[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2020, 13: 207-214.

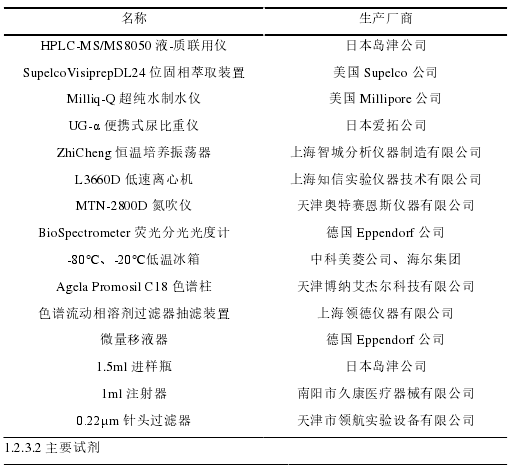

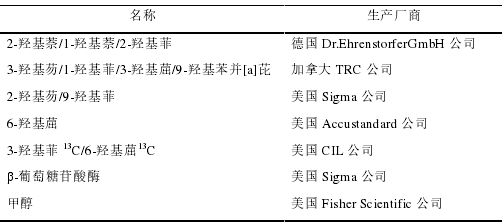

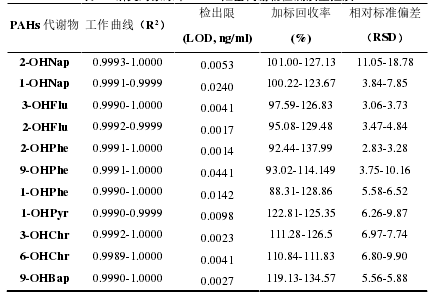

[49] 成琳, 李金玉, 吕胜杰, 聂继盛,张红梅,孙建娅. 超高效液相色谱-串联质谱检测尿中多环芳烃羟基代谢物 [J]. 环境与职业医学, 2017, 34(11): 1004-1008.

[50] Guan W.-J., Zheng X.-Y., Zhong N.-S. Industrial pollutant emission and the major smog in China:from debates to action [J]. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2017, 1(2): e57.

[51] Wang Y., Zhao H., Wang T., Liu X., Ji Q., Zhu X., Sun J., Wang Q., Yao H., Niu Y., Jia Q., Su W.,Chen W., Dai Y., Zhi Q., Wang W., Li Y., Gao A., Duan H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsexposure and hematotoxicity in occupational population: A two-year follow-up study [J]. ToxicolAppl Pharmacol, 2019, 378: 114622.

[52] Zhao G., Chen Y., Wang S., Yu J., Wang X., Xie F., Liu H., Xie J. Simultaneous determination of11 monohydroxylated PAHs in human urine by stir bar sorptive extraction and liquidchromatography/tandem mass spectrometry [J]. Talanta, 2013, 116: 822-826.

[53] Oliveira M., Slezakova K., Delerue-Matos C., Pereira M. C., Morais S. Children environmentalexposure to particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and biomonitoring in schoolenvironments: A review on indoor and outdoor exposure levels, major sources and health impacts[J]. Environ Int, 2019, 124: 180-204.

[54] Oliveira M., Costa S., Vaz J., Fernandes A., Slezakova K., Delerue-Matos C., Teixeira J. P., CarmoPereira M., Morais S. Firefighters exposure to fire emissions: Impact on levels of biomarkers ofexposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and genotoxic/oxidative-effects [J]. J Hazard Mater,2020, 383(5): 121179.

[55] Duan X., Yang Y., Wang S., Feng X., Wang T., Wang P., Ding M., Zhang H., Liu B., Wei W., YaW., Cui L., Zhou X., Wang W. Dose-related telomere damage associated with the genetipolymorphisms of c GAS/STING signaling pathway in the workers exposed by PAHs [J].Environ Pollut, 2020, 260: 113995.

[56] Wang W., Wang P., Wang S., Duan X., Wang T., Feng X., Li L., Zhang Y., Li G., Zhao J., Li L.,Wang Y., Yan Z., Feng F., Zhou X., Yao W., Zhang Y., Yang Y. Benchmark dose assessment for cokeoven emissions-induced telomere length effects in occupationally exposed workers in China [J].Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2019, 182: 109453.

[57] Zhou Y., Liu Y., Sun H., Ma J., Xiao L., Cao L., Li W., Wang B., Yuan J., Chen W. Associations ofurinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites with fractional exhaled nitric oxide anexhaled carbon monoxide: A cross-sectional study [J]. Sci Total Environ, 2018, 618: 542-550.

[58] Nie J., Li J., Cheng L., Deng Y., Li Y., Yan Z., Duan L., Niu Q., Tang D. Prenatal polycyclic aromatichydrocarbons metabolites, cord blood telomere length, and neonatal neurobehavioral development[J]. Environ Res, 2019, 174: 105-113.

[59] Jeng H. A., Pan C. H., Chang-Chien G. P., Diawara N., Peng C. Y., Wu M. T. Repeatemeasurements for assessment of urinary 2-naphthol levels in individuals exposed to polycycliaromatic hydrocarbons [J]. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng, 2011, 46(8):865-873.

[60] Rappaport Sm W. S., Serdar B. Naphthalene and its biomarkers as measures of occupationalexposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. J Environ Monit 2004, 6(5): 413-416.

[61] Unwin J., Cocker J., Scobbie E., Chambers H. An assessment of occupational exposure topolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the UK [J]. 2006, 50(4): 395-403.

[62] Campo L., Rossella F., Pavanello S., Mielzynska D., Siwinska E., Kapka L., Bertazzi P. A.,Fustinoni S. Urinary profiles to assess polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure in coke-ovenworkers [J]. Toxicol Lett, 2010, 192(1): 72-78.

[63] Li X., Jia S., Zhou Z., Hou C., Zheng W., Rong P., Jiao J., Yu J. The Gesture Imitation in Alzheimer’sDisease Dementia and Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment [J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2016, 53(4):1577-1584.

[64] Aprahamian I., Ladeira R. B., Diniz B. S., Forlenza O. V., Nunes P. Cognitive Impairment inEuthymic Older Adults With Bipolar Disorder: A Controlled Study Using Cognitive ScreeningTests [J]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry,, 2014, 22(4): 389-397.

[65] Schikowski T., Altug H. The role of air pollution in cognitive impairment and decline [J].Neurochem Int, 2020, 104708.

[66] Pan X., Luo Y. Secondhand Smoke and Women's Cognitive Function in China [J]. Am J Epidemiol,2018, 187(5): 911-918.

[67] Wingbermuhle R., Wen K. X., Wolters F. J., Ikram M. A., Bos D. Smoking, APOE Genotype, andCognitive Decline: The Rotterdam Study [J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017, 57(4): 1191-1195.

[68] Anstey Kj M. H., Cherbuin N. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for dementia and cognitivedecline meta-analysis of prospective studies [J]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry,, 2009, 17(7): 542-555.

[69] Guo Y., Xu W., Liu F. T., Li J. Q., Cao X. P., Tan L., Wang J., Yu J. T. Modifiable risk factors forcognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospectivecohort studies [J]. Mov Disord, 2019, 34(6): 876-883.

[70] Yaffe K., Laffan AM., Harrison SLC., Redline S., Spira AP., Ensrud KE., Ancoli-Israel S., StoneKL. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia iolder women [J]. JAMA, 2011, 306(6): 613-619.

[71] Sterniczuk R., Theou O., Rusak B., Rockwood K. Sleep disturbance is associated with incidentdementia and mortality [J]. Current Alzheimer research, 2013, 10(7): 767-775.

[72] Potvin O., Lorrain D., Forget H., Dubé M., Grenier S., Préville M., Hudon C. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults [J]. Sleep, 2012, 35(4):491-499.

[73] Baumgart M., Snyder H. M., Carrillo M. C., Fazio S., Kim H., Johns H. Summary of the evidenceon modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective [J].Alzheimers Dement, 2015, 11(6): 718-726.

[74] 张红明, 李卫星. 焦炉工人神经行为改变及其影响因素研究 [J]. 环境与职业医学, 2011,28(4): 205-209.

[75] Keir JLA., Akhtar US., Matschke DMJ., Kirkham TL., Chan HM., Ayotte P., White PA. ElevatedExposures to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and other Organic Mutagens in OttawaFirefighters Participating in Emergency, On-Shift Fire Suppression [J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2017,51(21): 12745-12755.

[76] Navarro KM., Cisneros R., Noth EM., Balmes JR., Hammond SK. Occupational Exposure tPolycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon of Wildland Firefighters at Prescribed and Wildland Fires [J].Environ Sci Technol, 2017, 51(11): 6461-6469.

[77] Kameda T. Atmospheric Chemistry of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Related Compounds[J]. Journal of Health Science, 2011, 57(6): 504-511.

[78] Kameda Y., Shirai J., Komai T., Nakanishi J., Masunaga S. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatichydrocarbons: size distribution, estimation of their risk and their depositions to the humanrespiratory tract [J]. Sci Total Environ, 2005, 340(1-3): 71-80.

[79] Liu Y., Zhu L., Shen X. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in indoor and outdoor air ofHangzhou, China [J]. Environmental science technology, 2001, 35(5): 840-844.

[80] Li W., Wang C., Wang H., Chen J., Shen H., Shen G., Huang Y., Wang R., Wang B., Zhang Y.Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rural and urban areas of northern China [J].Environmental Pollution, 2014, 192: 83-90.

[81] Gao P., Da Silva E., Hou L., Denslow N. D., Xiang P., Ma L. Q. Human exposure to polycyclicaromatic hydrocarbons: Metabolomics perspective [J]. Environ Int, 2018, 119: 466-477.

[82] Yan D., Wu S., Zhou S., Tong G., Li F., Wang Y., Li B. Characteristics, sources and health riskassessment of airborne particulate PAHs in Chinese cities: A review [J]. Environ Pollut, 2019, 248:804-814.